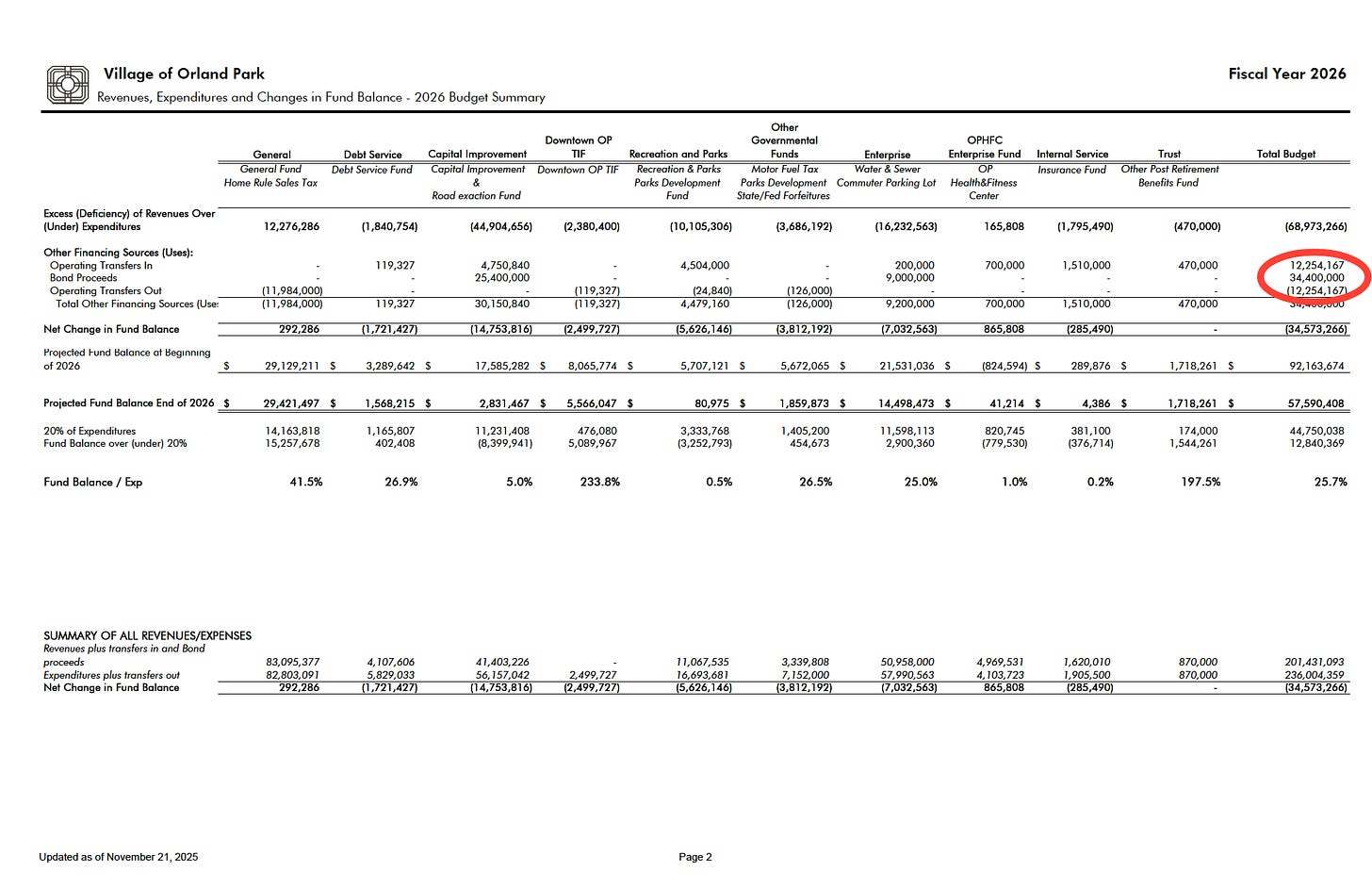

In just two months, the Orland Park Board approved borrowing that will nearly double the village’s existing debt.

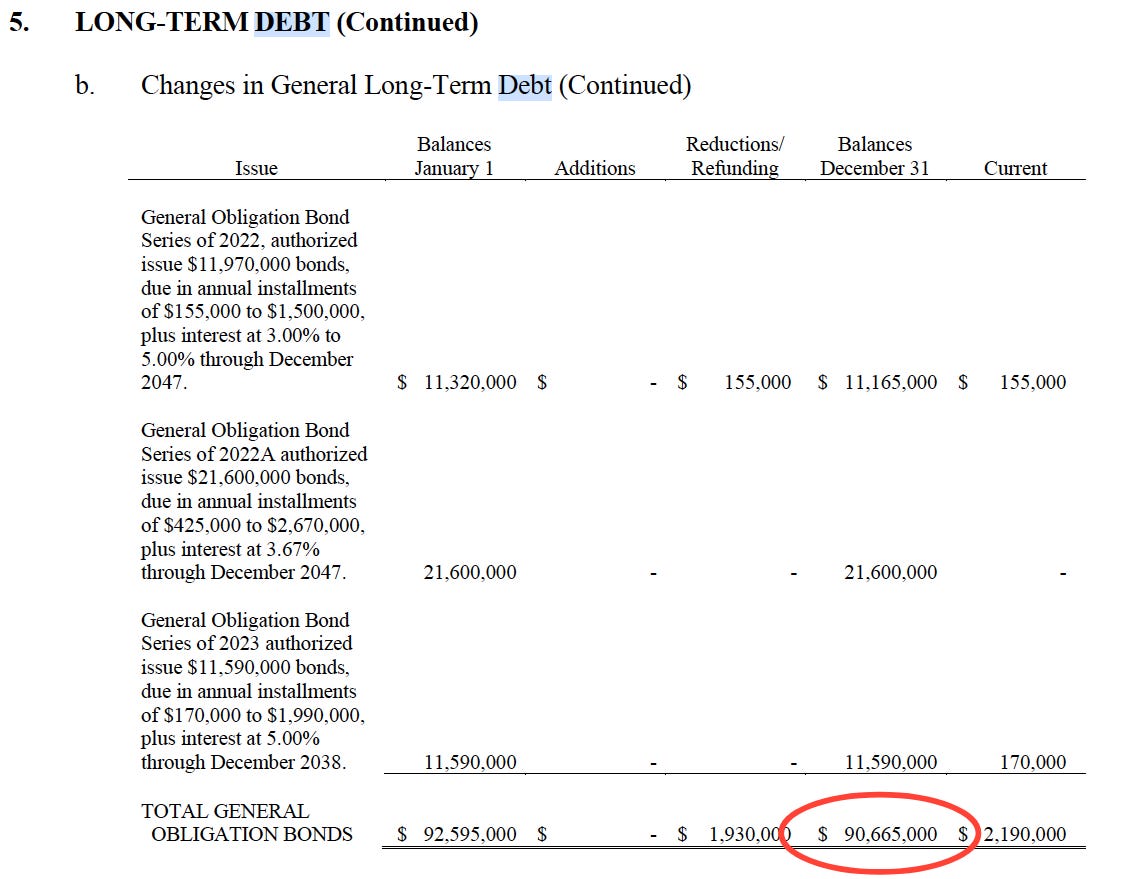

By the end of 2024, Orland Park carried about $91 million in outstanding general obligation bond debt — debt backed directly by taxpayers. According to the village’s own auditors, 2024 closed as a surplus year, with rollovers carrying available funds into 2025.

Then came October. Then December.

Two bond ordinances.

More than $82 million in new general obligation borrowing authority.

Approved weeks apart.

This was not a continuation of long-standing financial strain.

It was a choice made all at once.

October: Borrowing Without a List

The first bond ordinance came in October. It authorized $42 million in new general obligation debt.

But when the vote was taken, no capital projects were cited for that borrowing.

The borrowing moved forward.

The justification did not.

A trustee asked a straightforward question: could the public be given a breakdown of what the $42 million would be used for?

The response was lengthy. It referenced prior discussions, debt servicing, and a five-year plan approved in 2023. But it never named a single project.

What the explanation described was timing, not necessity.

The village had already paid for the projects being referenced — without issuing debt — and still closed 2024 with a surplus and rollovers carried into 2025. The spending itself did not create a shortfall. Issuing debt afterward didn’t make those projects possible. It simply replaced cash spending with long-term borrowing.

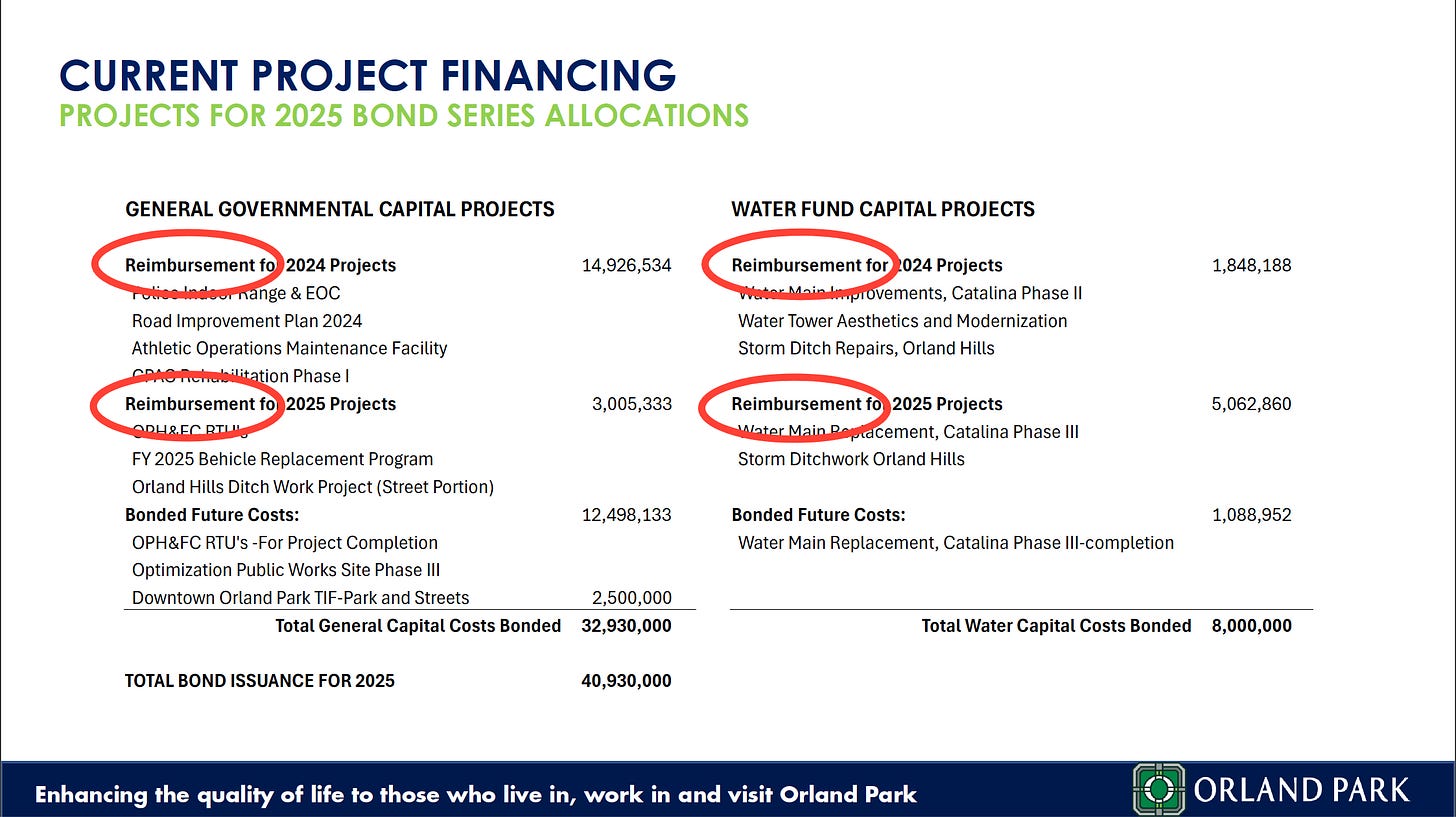

Subsequent materials confirm this point. The borrowing was tied largely to reimbursements for projects already completed (and paid for) in 2024 and 2025.

That isn’t planning for construction.

It’s refinancing decisions after the fact.

This wasn’t about running out of options.

It was about choosing debt.

“Planned” — According to Which Plan?

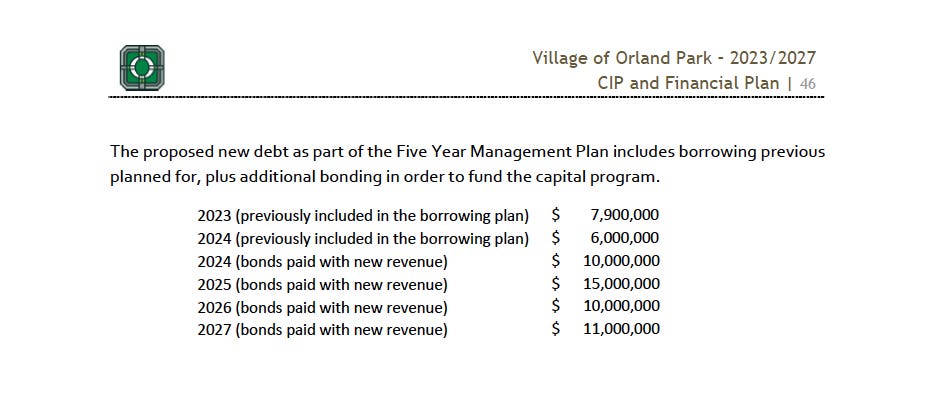

Officials described the October borrowing as planned. So we went to the plan they referenced: the Village’s Five-Year Capital Improvement Plan and Financial Plan.

What it shows are capital needs — individual projects spread across years with modest dollar amounts attached to each one.

Road repairs.

Facility upgrades.

Design work.

Maintenance projects.

Hundreds of thousands at a time. Sometimes a few million. Always itemized.

What it does not show is a $42 million bond issuance.

It does not show a consolidated borrowing action.

It does not show a schedule tying two years of projects to that amount of debt.

The Village Manager said this debt was “supposed to be bought in 2024 and 2025.” But the five-year plan does not show borrowing at anything close to that scale in those years. There is no line item, no aggregation, no model showing two years of debt totaling $42 million.

The closest thing to a borrowing reference is a summary table with much smaller annual assumptions — figures that do not match what was approved in October.

In other words, the plan outlines possibilities.

The bond ordinance authorized certainty.

Calling that borrowing “previously planned” blurs a critical distinction:

planning identifies options; borrowing commits taxpayers.

December: The Budget Doesn’t Match the Borrowing

Two months later, the board approved borrowing again — this time $40.5 million in new general obligation debt.

Unlike October, the December ordinance did list intended uses. And this time, officials framed the borrowing differently. They said this debt was for 2026.

So again, we went to the governing document — the Fiscal Year 2026 budget.

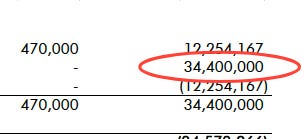

The budget’s own summary page lists total bond proceeds of $34.4 million, not $40.5 million.

Those numbers do not match.

And this isn’t a technicality.

Before 2026 has even begun, the board has already authorized more borrowing than the budget it approved contemplates.

This cannot be attributed to prior administrations.

This budget belongs to the current one.

They wrote it.

They adopted it.

And they exceeded it.

Just as in October, the explanation offered at the meeting does not align with the documents used to justify the borrowing.

The pattern is the same:

Certainty in debt.

Ambiguity in planning.

Accountability deferred until after the vote.

Debt Chosen — Even as New Revenue Arrives

And this didn’t happen in a vacuum.

It came after the village expanded its revenue base:

A new local grocery tax,

An increased property tax levy,

and water rate increases now expected to follow.

This was not a case of the village running out of money.

New revenue was already coming in.

Still, the board chose debt.

And even then, the public was never shown a consolidated plan — not one document tying the borrowing together, not one explanation showing why this amount was required or why it had to be approved all at once.

What was offered instead were assurances, references to prior discussions, and broad authorization language — but not a plan that matched the commitment being made.

Officials asked residents to accept certainty in debt without certainty of purpose.

Authority was granted.

Accountability was postponed.

Votes came first.

Clarity never did.

Thank you for reading another page in The OPen Record.

Other articles on the Village: